There are at least 41 threatened or endangered species in Alberta.

Habitat loss is usually the greatest threat to wildlife, but that might not be true for caribou.

Four caribou subspecies exist in Canada: woodland, barren ground, Peary, and Grant’s caribou. Only woodland caribou exist in Alberta.

Our province is home to 15 woodland caribou ranges. Four populations are stable on these ranges, nine are declining, and two are declining so much that they are near extirpation.

Back in 2013, a study estimated that Alberta’s woodland caribou population is very uncertain, with populations declining about 50 percent every eight years. And these predictions have been borne out.

Caribou were first listed as threatened under the Wildlife Act in 1985 due to habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, but who is to blame for the loss of critical habitat?

Climate Change Versus Habitat Change

Melanie Dickie, a senior caribou ecologist for the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute and the lead author of a new paper published in the Global Change Biology, suggests that climate change might be speeding up the decline of caribou populations.

Dickie uses Alberta’s population of white-tailed deer to support this claim.

In the late 1990s, white-tailed deer were rare in the northern boreal forest and were mostly restricted to the southern portion of the province.

By the 2000s, the population of white-tailed deer in both northern Alberta and Saskatchewan skyrocketed.

However, the two regions differed in one regard – habitat disturbance.

Dickie found that there were almost four times as many industrial disturbances on the Alberta side of the border than in Saskatchewan (e.g. cutlines, seismic lines, clearcuts and industrial infrastructure.)

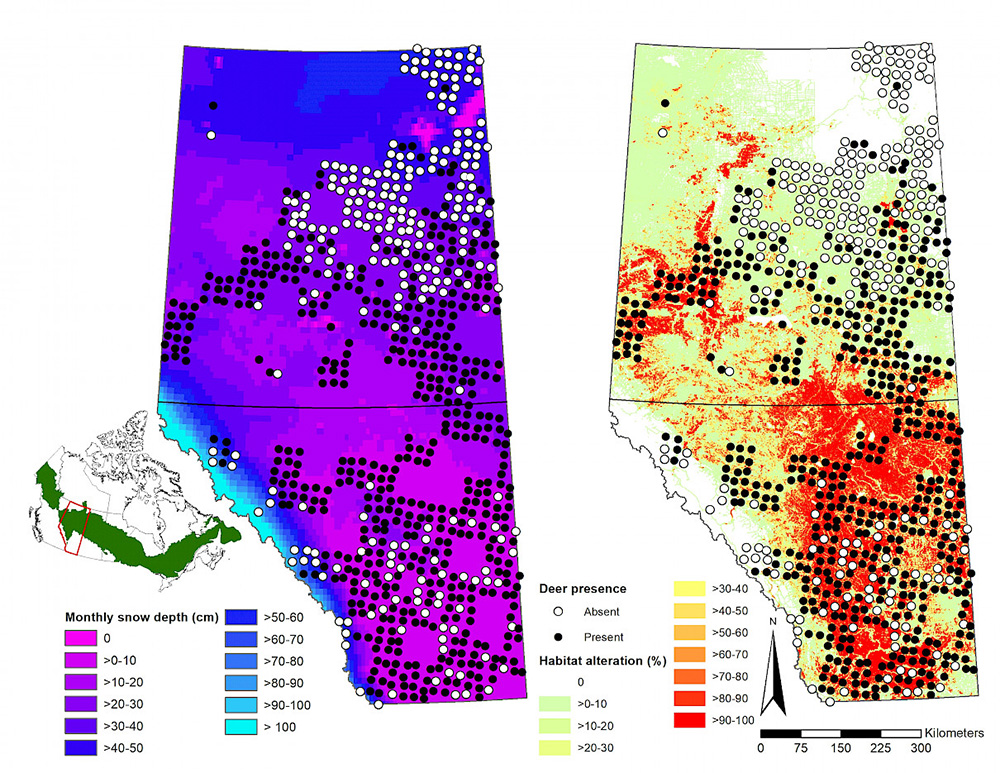

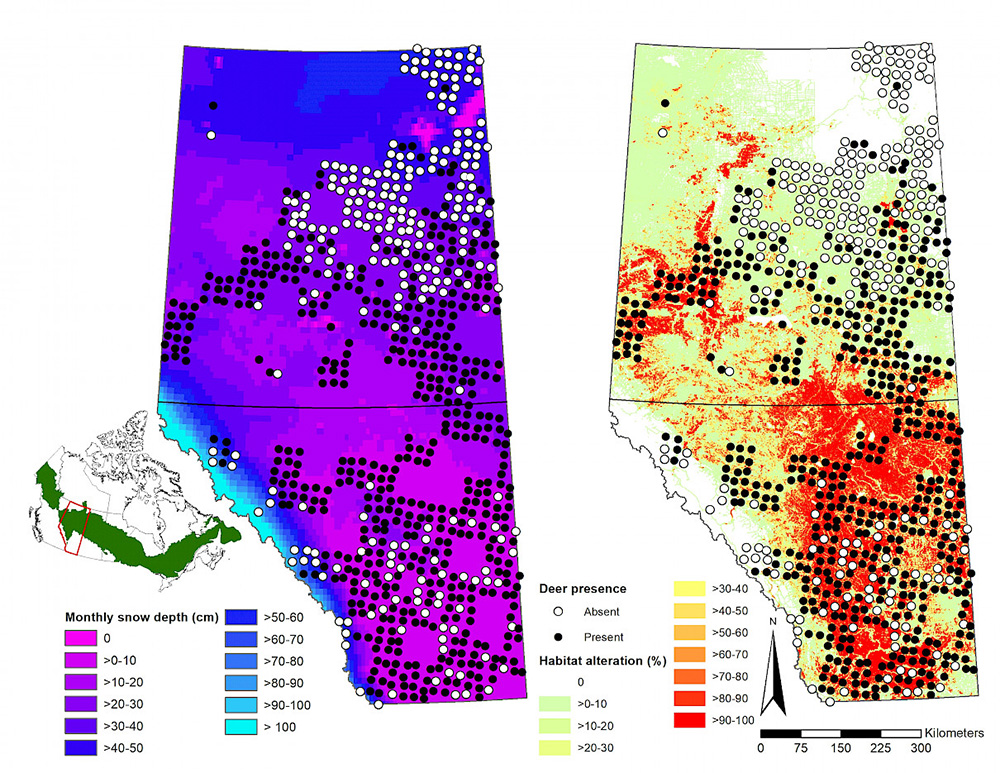

Between 2017 and 2021, Dickie’s team used a network of 300 wildlife cameras to capture tens of thousands of photos of white-tailed deer to estimate white-tailed deer density.

The researchers noticed that the north-south temperature change had more of an impact on white-tailed deer populations than east-west differences in human disturbances, like industrial activity.

“We found far fewer deer in places where the climate was snowier and colder. We did not find an effect from habitat alteration. It was half the magnitude of the climate impact,” Dickie told Global News.

So, what does this have to do with caribou?

“The expansion of white-tailed deer into the boreal forest has been linked to caribou declines. Deer are ecosystem disruptors in the northern boreal forests. Areas with more deer typically have more wolves, predators of caribou—a species under threat. Deer can handle high predation rates, but caribou cannot,” Dickie explained to the University of British Columbia.

So, for whitetail deer, habitat expansion was less about industrial disturbance (after all, whitetail deer are found in cities all over North America) and more about cold temperatures limiting their ranges.

As the climate continues to warm, whitetail deer populations will march northward, intruding into caribou habitat and bringing wolves with them.

A New Approach To Caribou Preservation

To save our province’s caribou, Dickie says tough choices need to be made, such as killing more wolves, hunting more deer, or creating a haven for caribou in the north where there are fewer white-tailed deer.

“There are some real social, economic and ethical considerations for all of these various management options,” said Dickie.

Between 2020 and 2021, the province made the controversial decision to kill over 800 wolves in an attempt to save its caribou.

According to a paper on western Canada’s caribou population, the cull was effective, and caribou numbers have increased by over 50 percent since 2020.

However, culls and hunts aren’t the only way to save our province’s caribou.

Parks Canada is currently in the design and construction phase of a program to breed caribou in captivity.

To be more specific, the agency aims to restore the Tonquin woodland caribou herd in Jasper National Park to 200 caribou within five to ten years by breeding the animals in captivity.

The Tonquin herd lives in a high-altitude area too cold for whitetail deer.

If successful, the program would bring the herd’s population to a sustainable level within the decade and pave the way for similar programs elsewhere in the province.

But the real long-term solution to saving our woodland caribou is not in killing wolves, or even remediating cutlines and clearcuts. To save our caribou, we need to halt the steadily increasing temperatures that result from our changing climate.

Unless we show real progress on the climate front, small patchwork solutions will do little in the long term to save Alberta’s caribou population.