David Thompson is perhaps Alberta’s most famous explorer. His accomplishments are legendary and shape the Alberta we know and love today.

Thompson walked or paddled over 80,000 km (50,000 miles) in his life, averaging way more than the 10,000 steps a day people monitor on their Fitbit.

Thompson mapped most of western Canada, parts of the east and the northwestern United States. But unfortunately, like many trailblazers, his achievements were only recognized after his death.

His efforts in western Canada between 1784-1812 earned Thompson the moniker “the greatest land geographer who ever lived.” He mapped a route to Lake Athabasca, discovered the Columbia River, and found a path to the Pacific Ocean.

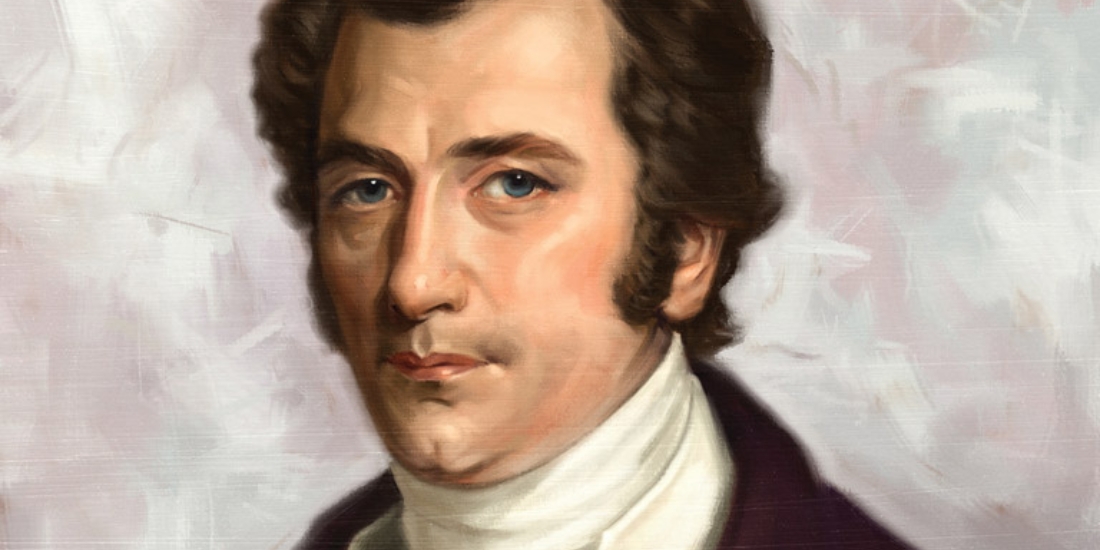

But who was the man behind these accomplishments?

Thompson was born on April 30, 1770, in Westminster, England. His father died when Thompson was just two years old. His widowed mother had to raise Thompson and his older brother alone.

At the age of 7, Thompson began school at the Grey Coat Hospital. After graduating, he continued his education at the Grey Goat mathematical school.

Thompson polished his mathematics, trigonometry, geometry, and navigation skills there. He was a complete nerd with a thing for numbers and maps.

These two skills eventually earned Thompson a job with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which was in the fur trade business.

Eventually, Thompson’s job at the HBC led him to Canada. He set foot on Canadian soil in Churchill on September 2, 1784. Thompson worked as an apprentice secretary for the HBC and frequently travelled between fur trade depots.

When he was 17, Thompson left Churchill and walked and paddled across the prairies to the Alberta foothills. He camped through the winter with the Piikani people in a tent, listening to stories about the Plains Indigenous peoples as the fire burned to stay warm.

Thompson also stopped over at the Cumberland House in Saskatchewan. During his time there, Thompson seriously fractured his leg and was forced to stay put. But this didn’t stop Thompson from continuing his nerdish ways.

While recovering, Thompson received tutoring from the HBC’s surveyor Philip Turnor. He helped Thompson further hone his mathematics, astronomy, and surveying skills. Turnor was like the Yoda to Thompson’s Luke.

But his time at the Cumberland House wasn’t without its setbacks. Thompson also lost vision in his right eye while at the Cumberland House. Staring at maps all day will do that to a person.

When an apprentice graduated, the HBC would customarily offer fine clothes as a gift. When Thompson graduated in 1790, he wanted a set of surveying tools instead of new threads.

Since the HBC liked him so much, they gave him both as gifts.

But Thompson’s good standing with the HBC wouldn’t last forever. In 1979, the HBC requested that Thompson stop surveying and focus on the fur trade.

This didn’t sit well with Thompson, so he walked 80 miles through the snow to join the HBC’s competitor, the North West Company (NWC). With his new employer, Thompson got the best of both worlds and could work as a fur trader and surveyor.

For the next few years, Thompson surveyed the land, traded furs, and led expeditions into the Rocky Mountains. While at Île-à-la-Crosse, a trading post in Saskatchewan, Thompson met Charlotte Small.

Small was a 13-year-old Metis girl. Her father was a member of the NWC, and her mother was an unnamed Cree woman. On June 10, 1799, Thompson married Small.

Weird age gap aside, Thompson and Small had a great marriage. Explorers and traders usually abandoned their wives and children to lead lives in Canada or Europe, but not Thompson. The pair had 13 children and were married for 58 years until Thompson’s passing.

Soon after marrying Small, Thompson discovered and mapped the Columbia River. Eventually, he found a route to the Pacific Ocean.

In addition to making Thompson the first white man to travel the entire length of the Columbia River, this was a huge milestone for Canada’s fur trading business. It opened up new territories for companies like the NWC to trade with.

While returning to the NWC headquarters in Montreal, Thompson was interrupted by an angry group of Peigan people. Thompson was forced to find another route through the Rocky Mountains.

Thompson’s published journals also wrote of something mysterious on his journey to Montreal. In 1811, he recorded seeing large footprints near what is now Jasper, Alberta.

Thompson noted that these tracks had a small nail at the end of each toe. At first, he thought it was a bear, but Thompson was unconvinced.

“I held it to be the track of a large old grizzled bear; yet the shortness of the nails, the ball of the foot, and its great size were not that of a bear,” wrote Thompson in his published journals.

Many believe that the tracks Thompson found were that of the Sasquatch. Next time you hear something outside your tent in Jasper National Park, it might just be Sasquatch himself.

Thompson died in Montreal on February 10, 1857. In the few years before his death, he was forced to sell all his possessions to support his family, including his mapping tools that were practically a part of Thompson himself.

After Thompson passed, his wife followed just three months later.

Thompson’s life was full of adventure and discoveries, but his death went unnoticed along with his achievements. He was buried in an unmarked grave and never got the chance to finish his book capturing his 28 years in the fur trade.

But J.B. Tyrrell, a geologist, knew of Thompson and his accomplishments. He wanted the rest of the world to know too. In 1916, Tyrrell published Thompson’s notes as David Thompson’s Narrative.

Tyrrell also placed a tombstone to mark Thompson’s grave in 1926. The following year, the federal government named Thompson a National Historic Person.

Even if Thompson’s death went unnoticed by those around him, he was well-known and respected by Canada’s First Nations. He even picked up four of their languages, including Blackfoot, Kootenay, Chipewyan, and Mandan.

To the Salish Indigenous peoples of British Columbia, Thompson was Koo-koo-sint, or “The Man Who Looks at Stars.”

For a man constantly chasing the stars on the horizon, there is no better name for Thompson.