We’ve had a severe shortage of rain and snow for going on three years, and the resulting drought is ravaging Alberta, especially in the southern part of the province.

It hasn’t been this dry in southern Alberta for 50 years, according to the Oldman River Watershed Council.

Not only is water in short supply, but the drought and extreme temperatures of this past summer fueled unprecedented numbers and sizes of wildfires in the province.

The current low snow packs and a predicted unseasonably warm and dry winter mean 2024 may be a repeat of 2023 with extensive wildfires but even less water.

How Bad Is It?

The Oldman Reservoir is at the lowest water level since it was built in 1991.

Currently, the dam is only 26 percent full. It usually has more than twice this amount at this time of year. The dam relies on snowpack and runoff in the spring to fill it during the summer. The continued lack of snow in the drainage is expected to worsen the water supply for 2024.

Agriculture in southern Alberta is heavily reliant on using stored water for irrigation, and the already low levels of water are wreaking havoc on livestock and crops.

Ninety percent of the water pulled out of the Oldman River by humans is used for irrigation.

To date, 20 municipalities in the province have declared agricultural disasters.

The situation will likely only worsen, according to Doug Kaupp, the City of Lethbridge’s General Manager of water and wastewater.

The forecast for 2024 is “pretty grim,” according to Kaupp, due to El Niño, which usually means a warmer and dryer winter than normal. “Our best hope is that the El Niño is short-lived and that we get some higher than normal snow in the mountains,” said Kaupp.

El Niño is a natural warming in the Pacific Ocean which can raise the temperature and alter weather patterns across the planet.

In the South Saskatchewan River Basin, where the drought situation is even more severe, the Alberta Energy Regulator (AEN) has contacted industry water license holders to get a handle on their water needs for 2024 and issued this statement: “Industry should be proactive and plan for water shortages during 2024, including conserving water in their operations now,”

Alberta Environment and Protected Areas Minister Rebecca Schulz said in a press conference in September, “In the spirit of being transparent and really making sure that everybody knows the issues that we’re currently in and what we’re planning for next year, we’ve pulled together a group of water users right across the province to help us address what we might be seeing.”

And what they are seeing is serious.

Across the province, water shortage advisories have been issued for 51 water management areas, and Alberta is currently in Stage 4 of its water management plan.

This is one step removed from Stage 5, which under the Water Act means there is an emergency with a “significant risk to human health and safety due to insufficient water supply and water quality degradation,” according to the province’s dedicated drought website.

According to Schulz, “the Alberta government is planning for the worst-case scenario and hoping for the best.”

Their plan?

Right now, the government is asking for help with its drought modelling.

Other than asking for help and hoping for the best, no actual plans have been laid out at this point.

Hope or Action?

Conservation groups have been warning the provincial government for decades about ongoing impacts on watersheds. The risks have been known, but ignored.

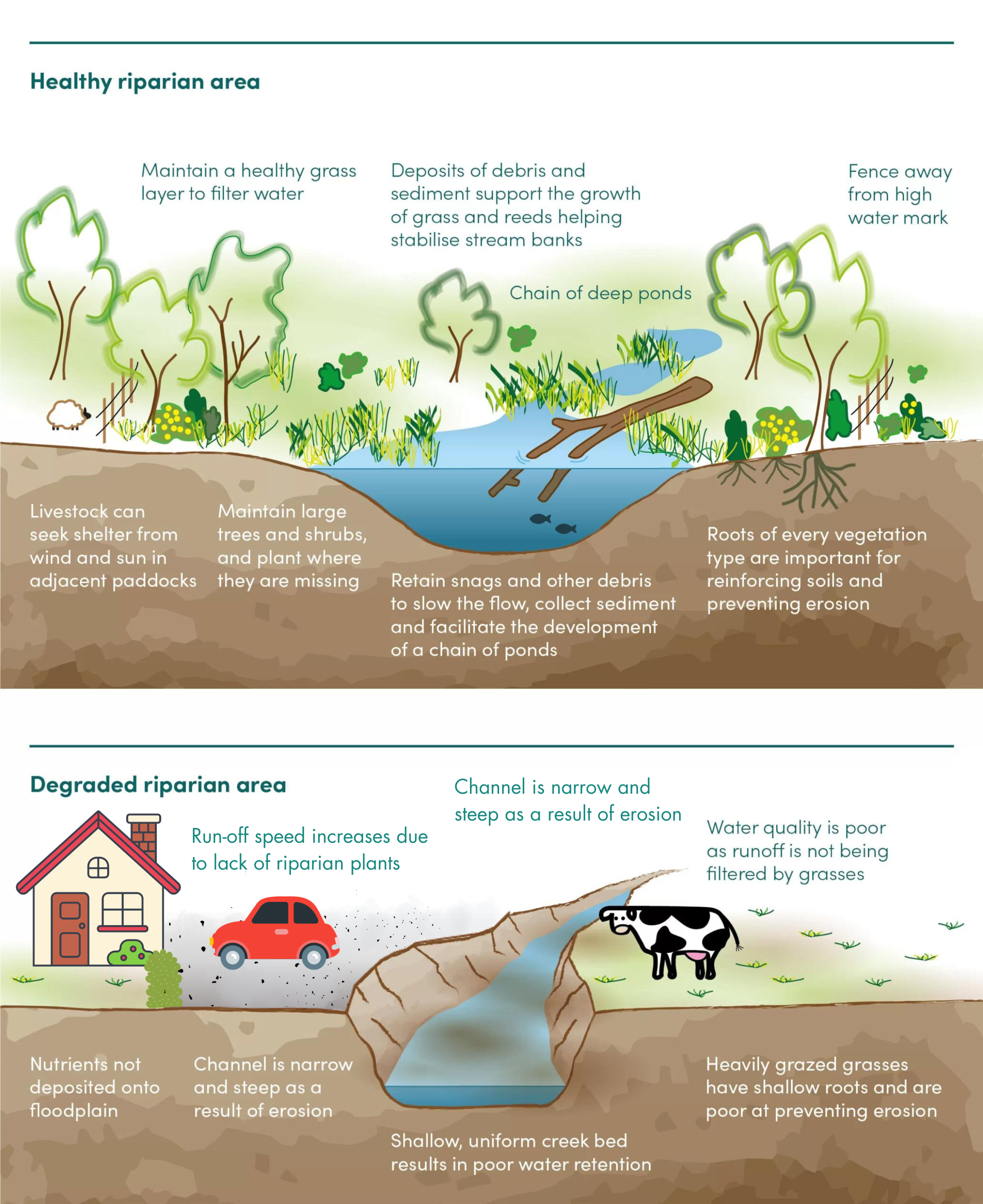

They include clearcutting in the foothills and loss of wetlands in the prairies, which raise the risk of floods in wet years and increase the risk of drought in dry years.

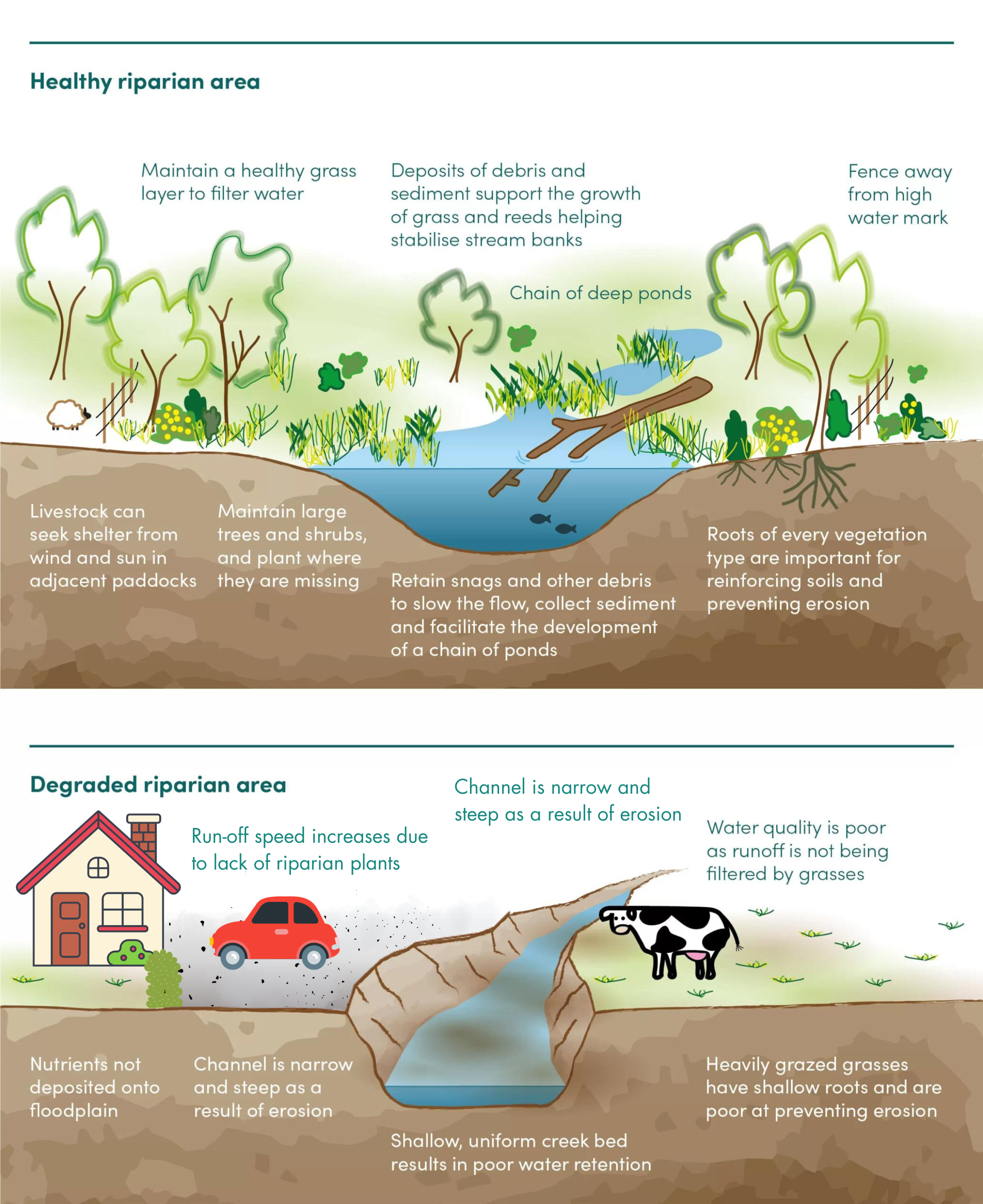

Having forested slopes in the foothills slows snowmelt in the spring, reducing the risk of floods and retaining groundwater during drier years.

Prairie sloughs also act as a buffer to flood and drought risk, moderating water fluctuations over time.

In the Canadian Prairies, wetland drainage for crop expansion has resulted in the loss of more than 40 percent of natural wetlands.

Draining wetlands, particularly small ones where water collects temporarily in the spring breaks the connections by which groundwater reserves are replenished.

The answer to tackling extreme water events like floods and droughts is to reduce carbon pollution in the atmosphere, maintain healthy forests and rejuvenate prairie wetlands.

Practices such as moving from large-scale industrial farming to smaller, sustainable, regenerative farming will also help conserve and manage water levels.

If the government wants a real plan for drought prevention, investing in prairie wetland restoration and reducing carbon pollution is an action that will do far more than wishing and hoping.