Over the past decade, a revolutionary movement has been gaining momentum in courts around the world.

This emerging legal concept holds immense promise for positive change but also faces significant scrutiny.

Let’s dive into it.

Since the 1800s, businesses have been treated like people in the eyes of the law. This made some people wonder why things like rivers, forests, or animals couldn’t be treated like people by the law.

The first breakthrough began with New Zealand’s Whanganui River being declared a legal person by the Kiwi courts in 2017.

You might wonder how a river can be granted personhood.

Though it may seem novel, the concept has been around for eons.

Many Indigenous cultures have long considered natural ecosystems entities in their own right, deserving of the same rights as humans, making the idea less far-fetched than it appears.

The Whanganui River was sacred to the Māori people, who have always viewed it as a person.

The Concept Spreads

The Whanganui ruling was the first that employed the ‘personhood’ perspective within a modern legal framework.

The court essentially declared the Whanganui River a “person” in legal terms, which meant that it now had a person’s legal rights, duties, and liabilities.

A river can’t speak for itself; therefore, to defend itself in court, it has representatives speak on its behalf.

In the case of the Whanganui, it had one Māori and one Crown spokesperson functioning as its guardians.

The guardians have been able to argue that polluting or damaging the river is equivalent to harming a legal person.

Because of their efforts, companies have been held accountable for their past digressions against the Whanganui’s rights to exist and to thrive free from harm.

More compensation has now been awarded for past damages without showing clear connections between those damages and their impacts on human beings.

The results have increased funding for stewardship and restoration efforts and protection from future polluting projects.

After the Kiwi ruling’s success, other countries soon followed suit.

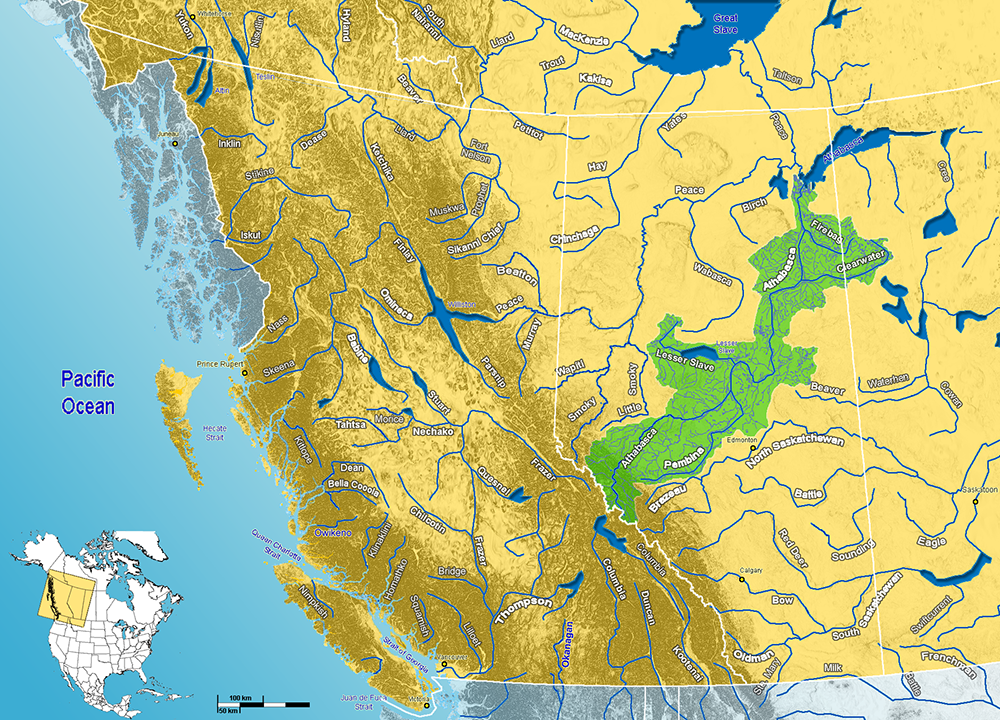

The Atrato River in Colombia and the Magpie River in Quebec have been among the growing list of rivers, lakes, and mountains to receive this unique status.

Now, the movement has touched ground in Alberta.

Hi, My Name Is Athabasca

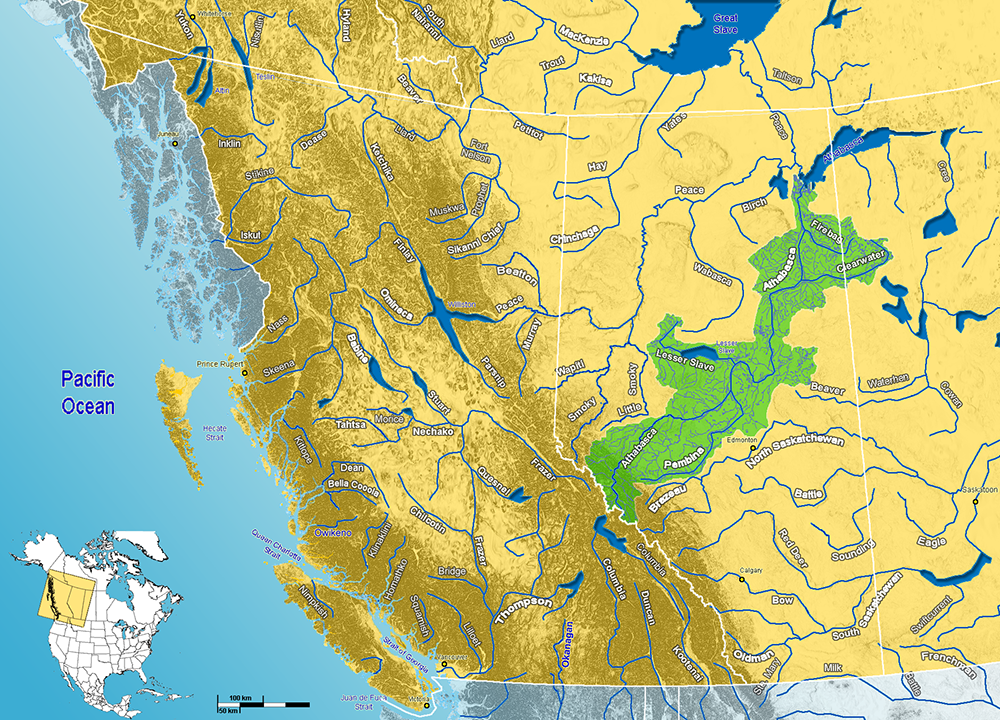

The Athabasca River Basin has asked the Alberta Energy Regulator to recognize it as a legal person.

The Athabasca River originates at the Columbia Icefield in Jasper National Park and flows more than 1,538 km before emptying into Lake Athabasca, the eighth-largest lake in Canada.

Keepers of the Water, the Alberta Wilderness Association, and Ecojustice have submitted the request on behalf of the Athabasca River to object to Canadian Natural Upgrading Ltd (CNUL)’s request for new permits to extend its Jackpine Mine for the next ten years.

Jackpine is an open-pit oil sand mine 70 km north of Fort McMurray.

“The process of renewing CNUL’s permits under EPEA and the Water Act gives the Regulator an important opportunity to assess the current and projected impacts of the Jackpine Mine on the environment and human health,” said Matt Hulse, a lawyer for Ecojustice

The Jackpine Mine is located on the east side of the Athabasca River, and it withdraws (on average) almost 50 million litres of water from the watershed daily. That’s as much water as almost 200,000 Canadians use in a day.

The Athabasca River Basin’s statement argues that CNUL’s application fails to provide critical information about the impacts of contaminants emitted from the mine, among many other concerns.

“It is critical that the Regulator has the information it needs to do this assessment properly,” said Ecojustice’s Hulse

The request also alleges discrepancies and gaps in information about how much water the mine uses.

Plus, no cumulative effects assessment about impacts on regional water quantity exists.

The claims on behalf of the Athabasca River Basin say that if the new permits are approved without further conditions set on CNUL to better protect the Basin, the river and the people who depend on it will suffer.

With so much at stake, Hulse said the decision to raise the river’s personhood wasn’t extreme.

“The fact that the Athabasca River Basin is bringing issues with CNUL’s application to the Regulator’s attention as a legal person may be new in Alberta, but it is consistent with the evolution of law in Canada and around the world.”

The Regulator does have the authority to recognize the Athabasca River Basin as a legal person.

The question is, will it?

Pros and Cons

Many believe that a legal framework acknowledging the rights of nature will protect the natural world from ecological damage, particularly by large companies.

However, there are pros and cons to extending personhood to nature.

The primary argument in favour of granting legal personhood is that being able to sue on behalf of nature:

Firstly, it honours Indigenous people’s relationships with their environment.

Secondly, it allows for environmental protection without having to prove that harm has been done to human beings.

Phillip Meintzer, Conservation Specialist with Alberta Wilderness Association, said, “Without legal personhood, it’s challenging for these crucial ecosystems to push back against further harm.”

One concern with the movement for natural phenomena to have “personhood” is that it implies a right to sue and to be sued.

For example, could the river then be liable for damage it causes in a flood? If so, are the river guardians paying for those damages?

Likely not, but it’s food for thought.

Then again, if the flood was caused by slope destabilization from clearcut logging or mining, is the river really at fault?

Things get complicated fast.

For Jesse Cardinal, Executive Director for Keepers of the Water and one of the people signing up to shoulder the costs in that scenario, Athasasca’s move to personhood is a no-brainer.

“Water is alive and should be treated as such; if we grant corporations legal personhood, we should certainly recognize—and protect—an ecosystem as important as the Athabasca River Basin.”