Imagine having to worry that the water in your home could make you, your kids and the rest of your family sick.

That’s what people in Mînî Thnî (formerly Morley) have had to worry about for decades. The community, located west of Calgary, plans to fix that by adding 25 more homes to the proposed Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation pipe water distribution system.

The community is taking action after a long history of boil water advisories.

In case you didn’t know, a boil water advisory is issued when a community’s water has, or could have, germs that can make you sick. If you are under a boil water advisory, you should drink bottled water or boil your tap water.

Boil water advisories are nothing new for the band. From 2001 to 2005 and again from 2006 to 2014, the people living in the Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation had to boil their water because it wasn’t safe to drink.

The 25 homes being added to the new pipe water distribution system will no longer rely on private wells previously under boil water advisories.

“It takes some homes that are on wells or cisterns right now off truck-haul delivery and gets them tied into the water distribution system, which is much more reliable and safer.” Blair Birch, with Stoney Tribal Administration, told the Rocky Mountain Outlook.

Birch explained that finding safe water in the community is tough, and some wells have harmful substances like Barium. Connecting homes to a distributed safe water source is the best way to solve these problems with wells and cisterns.

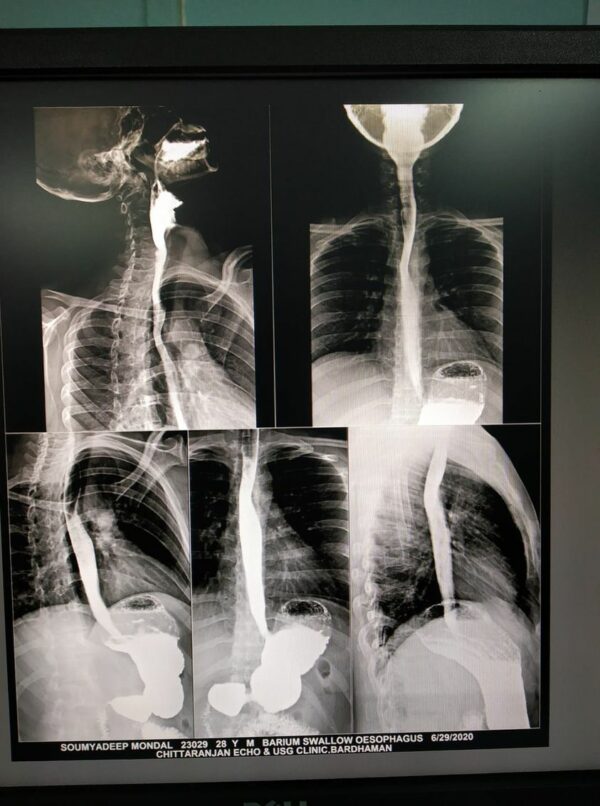

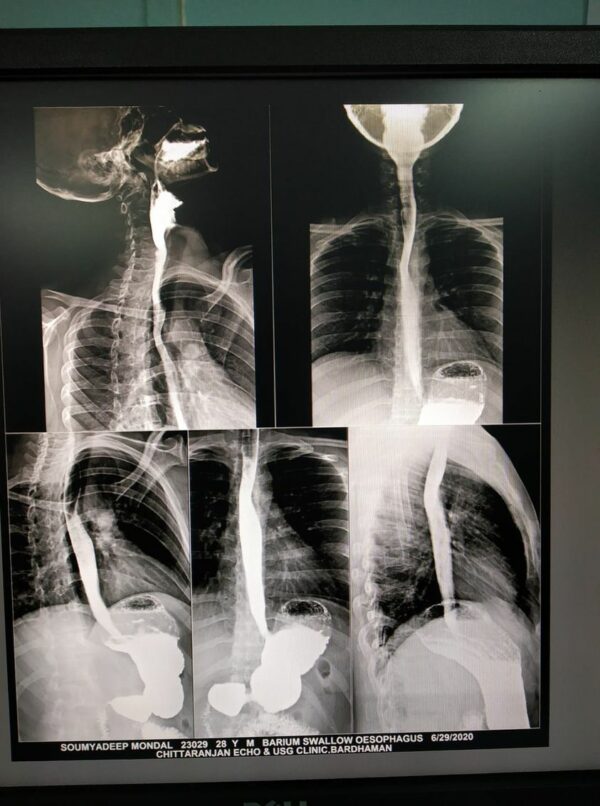

Barium Contamination

Barium is a soft, silvery metal. It is commonly used in medicine as barium sulphate, a white powder that makes organs visible when X-rayed. Barium sulphate is also popular in the oil and gas industry to make drilling mud used to lubricate the drill.

But you do NOT want, Barium, the metal in your water! Barium reacts quickly in water and is highly toxic.

Drinking or eating barium can cause vomiting, diarrhea, muscle weakness, difficulty breathing, and anxiety. Ingesting large amounts of barium can cause changes in heart rhythm, paralysis, and death.

According to studies referenced in Health Canada’s Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality, long-term exposure to barium is strongly linked to kidney-related issues.

Health Canada’s “safe drinking water” level for Barium is two mg/l for Barium.

But some wells on the Stoney reserves have recorded more than that amount. Other issues like surface drainage, clogged well screens, and problems with maintenance have also impacted water quality.

Taking Canada To Court

Over 1,000 people living in Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation have made damage claims as part of the federal class action lawsuit.

What did Canada do to deserve a class action?

Simple. Our governments have failed First Nations when it comes to supplying the basic human right of clean water.

A 2015 study found that First Nations reserves are 90 times more likely to be without running water. The lack of clean, safe water meant First Nations had a 26-fold higher rate of water-borne infections than other Canadians. The same study found that one in every three reserved-based community water systems was classified as posing a high risk for water quality.

The federal government regulates water quality for off-reserve communities but not for First Nations reserves.

While Canada has provided financial aid to improve water and wastewater systems for First Nations, the country has failed to provide continued funding to operate and maintain these systems.

The federal government’s financial aid model is like handing someone the keys to a brand-new Ferrari and walking away; leaving the person with the pricey insurance, maintenance and lease payments to worry about.

The Stoney class action covers the boil water advisories from November 27, 2001, to August 2, 2005, and again from October 20, 2006, to March 21, 2014.

In March of this year, Stoney Health Services held a three-day settlement signing blitz in Mînî Thnî.

As many as 300 people submitted claims daily. Some people claimed skin irritation, and others cited more serious health issues like organ failure and cancer.

Most of the water pipes and systems were built between 1999 and 2008. The community’s water system is divided into different areas: east, north, central Mînî Thnî, and Eden Valley and Big Horn.

According to a 2011 report, some homes in these areas were served by pipe water, but many houses had to rely on wells or water brought in by trucks.

Since then, more homes have been connected to pipe water.

In Mînî Thnî, the water distribution system covers the core area of the townsite, including schools, health centres, administration buildings, and more.

In Big Horn, the Nation started work this spring to connect all homes in the community to the water distribution system. As for Eden Valley, the Nation plans to connect all homes to piped water by 2027.

Birch said the Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation plans to expand the water distribution system further. This includes expansion south of the Trans-Canada Highway.

The proposed project is still in the preliminary design phase, but a request for a proposal is expected sometime after November. If everything goes as planned, construction will start next spring.

The project will be funded by Indigenous Services Canada, a government agency working to improve access to high-quality services for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.